Where do you go when you're not at home or work? Nowhere.

America's third places are vanishing at an alarming rate. The psychological and financial consequences of this loss run deeper than you might think...

Want more? As a paid member, you get access to my weekly Q&A column, plus monthly expert interviews, community discussions, and workbooks such as interactive PDFs, printable exercises, and templates.

When I lived in the East Village, I was a regular at the Tompkins Square Library. I read there, worked there, cried there, fell in love there, watched movies there, made friendships — lived life there. I knew all of the librarians — they gave the best book recommendations, asked about my work, and served as a comforting presence in the fraught period of my mid-twenties.

Libraries were mainstays of New York City culture — there were many locations, they were open seven days a week, and (most importantly) they were free. Everyone was welcome.

In 2023, mayor Eric Adams ended the 7-day New York Public Library service due to budget cuts. Some locations have also drastically reduced their hours. Now, if you want a place to spend a rainy Sunday or an early Monday afternoon, you’re stuck paying for a $7 latte or a $12 beer — or maybe, you’ll just start staying at home.

It's a story playing out across America — the slow disappearance of "third places," community spaces that exist outside of home and work where we gather, connect, and simply exist in public without spending a fortune.

What happens when just existing in public becomes a luxury?

Today, I want to explore what happens when the spaces and activities meant to connect us become increasingly unaffordable, and how this transformation affects not just our social lives but our financial decisions, too.

Where have all the hangout spots gone?

Where do you go if you’re not at school, work, or home? If you’re like most Americans, the answer is nowhere.

The term "third place" was coined by sociologist Ray Oldenburg in his 1989 book "The Great Good Place." He defined these spaces as informal public gathering places (beyond home and work) where people can gather and hang out.

Classic examples include cafés, pubs, community centers, barbershops, bookstores, parks, and libraries. Oldenburg argued that these spaces are essential for community vitality, civil society, and democracy itself.

But America's third places are disappearing at an alarming rate.

According to research from the Survey Center on American Life, less than half of Americans report having access to community gathering spaces in their neighborhoods.

The pandemic accelerated this trend dramatically. More than 110,000 restaurants and bars permanently closed during COVID-19. Many of these places were smaller establishments that couldn’t afford to stay open due to rent hikes.

In my current neighborhood, Williamsburg (which has a rich history intertwined with Puerto Rican immigration and culture), a cafe owner had to close her coffee shop, Buddies, due to a rent hike — one of the last Puerto Rican businesses in the area. This is just one small example of thousands.

But this isn't just about post-pandemic economics. It's the culmination of decades of urban development that has systematically undervalued community spaces in favor of profit-maximizing real estate and corporate chains. If you haven’t read the viral Cut article “It Must be Nice to be a West Village Girl,” I highly recommend it — it touches on this very trend.

Urban theorist David Harvey popularized the concept that modern cities are often deliberately designed to separate social classes and prevent community building — not accidentally, but as a feature of capitalism that prioritizes property values over human connection.

The numbers tell the story. From 2000 to 2024, commercial rents in urban centers increased by an average of 76%, adjusted for inflation — far outpacing the growth in median wages (19% over the same period). The result? Independent businesses that once served as neighborhood anchors can no longer afford to exist, replaced by corporate chains or luxury retail that can sustain the higher rents.

In many cases, young people and lower-income communities are hit hardest by all of this. Today's physical environment has become increasingly hostile to teenage existence — many places that kids would “hang out” after school (like malls) are closing, and activities that once cost pocket change cost $50-$100. When I was a teenager, the cost of a movie ticket was around $8. Today, they’re anywhere from $20-$30. Plus, many spaces (like coffeeshops) discourage teen presence with "no loitering" policies and design elements meant to prevent gathering.

Just a couple more examples of “funflation”:

The average resale price for concert tickets on SeatGeek has more than doubled since 2019 — up from $125 to $252 in 2023. It’s no longer uncommon to hear of people shelling out $1,000 on a single ticket.

The average NFL ticket is $377; last season the average ticket was $235.

In 2015, a family of four could visit Disney World for around $500 in today’s dollars. Today, the same family faces a $766 bill for four one-day peak-season tickets.

Let’s look at a contrast this — Europe. In places like Vienna, Barcelona, and Amsterdam, café culture remains vibrant and accessible. My friends in London can go to a pub after work and pay £5 for a pint. In places like Portugal, a glass of wine can cost as little as €1.

In these communities, public-facing businesses have a community function beyond profit maximization — something that has largely disappeared from American culture. And we're all poorer for it.

When every hobby needs its own line of credit

It's not just third places that are becoming unaffordable. The activities that once filled these spaces — our hobbies, interests, and pastimes — have seen similar price inflation that puts them increasingly out of reach.

I noticed this personally as my younger sister has gotten into knitting. I thought of knitting as a cheap, economically accessible way to make hats and scarfs. And boy was I wrong. In most cases, knitting was more expensive than just buying the product yourself. In the shops in New York, a single skein of wool can cost $30 or more.

Of course, there’s a degree of consumerism involved here, but the cost of admission for many hobbies has gone up. This phenomenon is known as "hobby inflation" — how recreational activities from fishing to photography, knitting to tabletop gaming have seen explosive price increases that outpace general inflation.

The causes vary by activity but share common themes: supply chain disruptions, increased popularity during the pandemic, rising raw material costs, and (in some cases) aggressive profit-taking by companies that recognize the emotional investment hobbyists have in their pursuits.

A recent New York Times article summed this up well: "Hobbies are, by definition, nonessential. Still, hobbies ameliorate the stressors of work, the news or family life. And they are intertwined with identity. Now, Americans may need to rethink their relationships to those activities.”

For many, hobbies aren't just ways to pass time; they're how we express ourselves, find joy, develop skills, and connect with others who share our interests. When the financial barrier rises, we lose not just leisure activities but potential pathways to identity formation and social connection.

The average American now spends around $100 monthly on their hobbies, whether that be reading, playing video games, cooking, or arts and drafts. For many, this spending has become a budget item that could be the first to go when their budget gets tight.

This price inflation isn't evenly distributed. Some activities — particularly those with higher barriers to entry like skiing, golf, or collecting — have seen the most dramatic increases, creating a two-tier system where certain hobbies function as status markers rather than accessible pastimes for everyone.

The impact goes beyond individuals — it affects the local economy of communities. Local game shops, craft stores, and specialty businesses that once offered both products and gathering spaces for enthusiasts struggle to survive as customers move to cheaper online alternatives or abandon hobbies altogether.

In short — this trend will just reinforce existing inequalities. If the ability to develop and maintain your interests becomes a luxury, we create a world where the pleasure and growth that come from pursuing passions are available only to those with disposable income.

When screens are all we can afford

So if outside is too expensive, where do you go? For many people, it’s online. Online communities, social media platforms, video games, and virtual reality offer spaces where people can gather, interact, and pursue interests.

Americans spent an average of 7.5 hours daily on digital media in 2024, up from 3.8 hours in 2010. For many, digital spaces have become the primary places for social interaction, particularly among younger generations.

There are some benefits to this digital shift. Online communities can connect people across geographic boundaries, provide support and belonging for those with niche interests, and offer alternatives to expensive physical spaces.

But digital spaces, for all their advantages, cannot fully replace physical third places. Research consistently shows that in-person interaction provides psychological and physiological benefits that digital connection cannot replicate.

Many people are aware of just how harmful screen time and digital addiction can be. It can make you more depressed, anxious, and lonely. Many of these platforms are designed to maximize engagement rather than genuine connection — these companies spend millions and millions of dollars to monetize your attention (and data).

As more people have become aware of just how horrible social media is (especially for young people), tech companies are now explicitly marketing their products as solutions to the very loneliness their platforms have helped create. Mark Zuckerberg recently suggested that Meta’s AI companions could “replicate true friendships”.

This approach treats loneliness as an individual problem with a tech solution rather than seeing it as a social issue stemming from economic and urban design choices that have systematically dismantled community spaces.

In other words — we've created a society where physical connection has become expensive, then offered digital substitutes that provide just enough connection to keep us functioning but not enough to truly thrive.

The loneliness epidemic (and what it costs us)

All these trends — the disappearance of third places, the increasing cost of activities, and the migration to the digital realm — have contributed to what U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy formally declared an "epidemic of loneliness" in 2023.

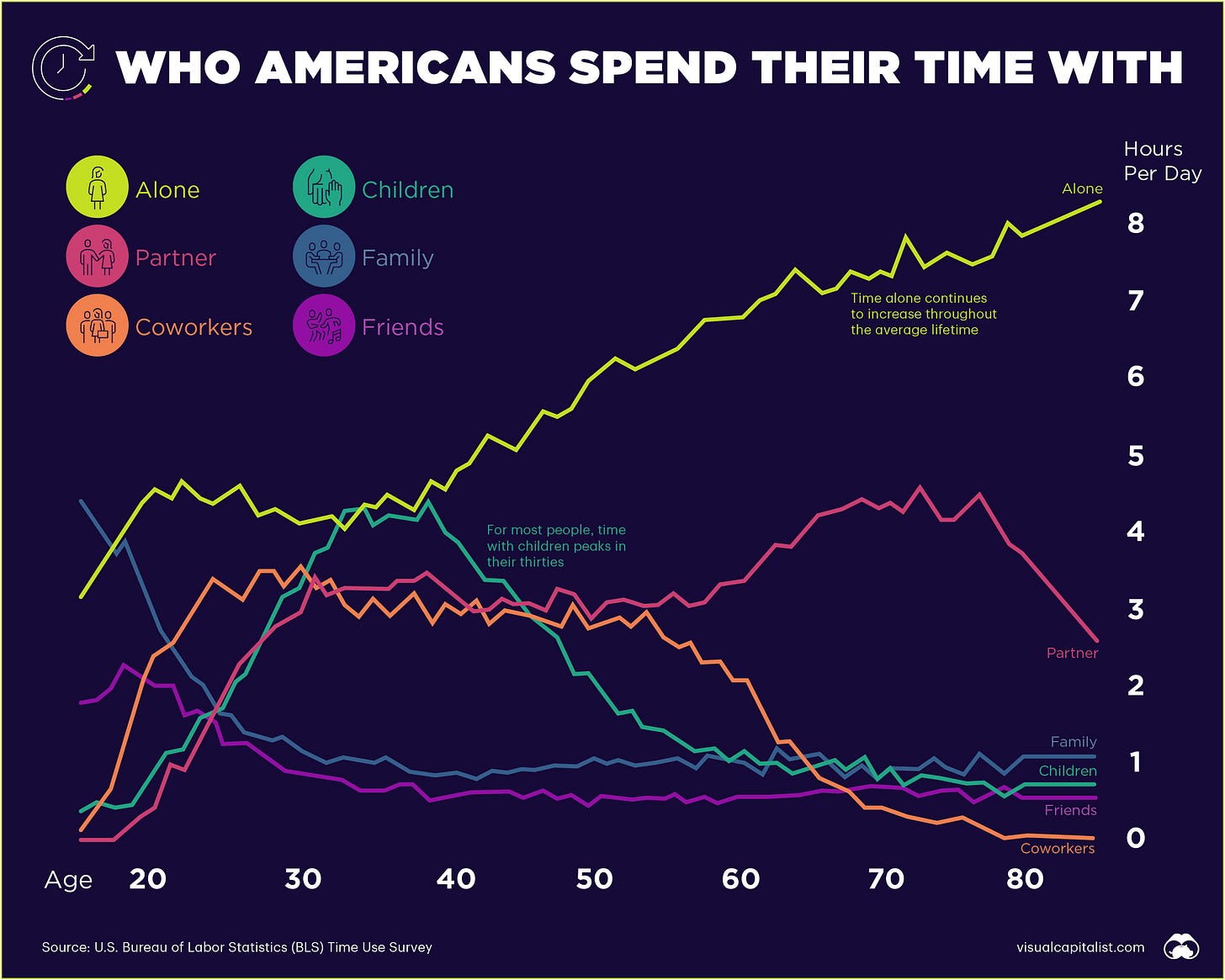

More than half of Americans report feeling lonely on a regular basis. Almost one in five Americans say they have no close friends, up from 12% a few years ago. Around 50% of Americans feel that their relationships aren't meaningful, and only 39% say they feel a sense of belonging in their communities

Many people (including myself) have experienced loneliness before, and it’s debilitating. It’s associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular disease, dementia, stroke, depression, anxiety, and premature death. The impact of being socially disconnected is similar to that caused by smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day.

Loneliness also imposes a massive economic burden. Loneliness costs the U.S. economy $460 billion annually from workplace absenteeism alone — not counting healthcare costs, reduced productivity, and increased social service needs.

But this epidemic isn't just a public health crisis — being lonely reshapes our financial behaviors in serious ways.

The weird things loneliness does to your money

As I've researched this topic, I've been struck by how loneliness influences financial decision-making — creating what I've come to think of as a "loneliness tax" that affects everything from daily spending to major financial choices.

1. It can increase consumption

We want to fit in. And when we don’t feel like we do (which can be lonely), we may spend more. Research shows that socially excluded individuals show greater preference for status-signaling products and experiences. In simple terms, when we feel lonely, we tend to buy things we think will help us connect or impress others.

This manifests differently for everyone, but the underlying psychology is similar: We try to buy our way out of loneliness, often with purchases that provide only temporary relief while creating longer-term financial strain.

Lonely consumers show some really interesting, distinct shopping patterns: They're more likely to choose anthropomorphized products (those with human-like characteristics), pay more for brands that provide a sense of belonging, and develop stronger attachments to service providers who offer personalized interaction.

2. It can increase risky money moves

Another study found that when people feel socially isolated, they're more likely to take more financial risks, make more impulsive purchases, and prioritize immediate gratification over long-term financial health

This helps explain why lonely people are also more vulnerable to financial scams. Socially isolated individuals are 5.5 times more likely to fall victim to investment fraud, often because the scammer provides the social interaction and validation they crave. The romance scam industry, which costs Americans over $1 billion annually, thrives on this vulnerability.

3. The "subscription economy" exploits our need for belonging

In a capitalistic society, if there’s a problem, there will be companies trying to make money off of it:

Membership clubs like Soho House sell exclusivity and social connection for $2,400+ annually.

Friend-finding apps like Bumble BFF monetize the basic human need to connect.

Rentafriend.com literally lets you hire people at $40/hour to serve as a temporary companion.

These services aren't inherently negative — they can provide genuine value for people struggling to connect. What's problematic is how they transform what was once freely available through community structures into premium services.

4. Financial collaboration decreases

One of the less obvious impacts of social isolation is how it reduces opportunities for financial collaboration. Historically, communities pooled resources through both formal structures (credit unions, buying clubs) and informal arrangements (childcare exchanges, tool libraries, meal sharing).

These economies provided money benefits while strengthening community bonds. As third places disappear and social connections weaken, these systems of mutual aid and resource sharing break down.

So, what can we do about it?

This all sounds pretty bleak, I know. But I'm not writing this newsletter just to document a trend — I want to explore what we can do about it, both individually and collectively.

What you (yourself) can do

While the roots of our loneliness epidemic are systemic, there are steps we can take ourselves to reduce both social isolation and it impact:

Take a look at your spending: Review your recent purchases with a critical eye: How many were motivated by a desire for connection or status rather than utility or joy? Often, when people think about cutting back or saving more, they think in pure dollar amounts and less in the value that spending could bring you. A $5 coffee consumed weekly at the same local café where you’re regular may offer far more connection than something else.

Invest strategically in connection: Rather than eliminating entertainment or social spending, redirect it toward experiences and organizations that provide genuine community. This might mean becoming a regular at a local business, joining a community organization like a garden club, recreational sports league, or volunteer group.

Create the third places you want to see: If third places don’t exist in your community, make them. You could have gatherings in your home or public spaces. You could start a walking group or book club. The possibilities are endless.

Practice intentional digital consumption: We would all stand to benefit getting off our phones more. But rather than rejecting social media entirely, you could use it to complement rather than replace physical connection.

Develop connection skills: Many of us have lost the art of casual social interaction (only made worse during the pandemic) making third places feel intimidating even when they are accessible. Rebuilding these skills takes practice! It’s ok if it feels a little awkward at first! As an extroverted journalist who used to cold call people, I still get a little shy when I’m in a new place or event. Most people want to connect — you may just have to open the door.

What we can all advocate for

While individual actions matter, addressing the root causes of increasing loneliness requires collective action:

Support zoning reforms that prioritize community spaces: Many cities have zoning laws that make it difficult to establish affordable third places in residential areas. Supporting mixed-use zoning and permitting reforms can create more opportunities for community businesses to thrive where people actually live.

See community spaces as essential: Libraries, parks, community centers, and public parks should be seen as essential infrastructure for community well-being. Vote for candidates that care about these spaces. Donate to local businesses – like the library!

Prioritize community-owned businesses: Supporting these businesses — from cooperative bookstores to community-owned cafés — helps preserve gathering spaces that prioritize social value alongside profit.

Recognize connection as a public health priority: Some communities have begun integrating social connection into public health initiatives. Supporting these efforts through advocacy and participation helps build recognition of connection as a necessity rather than a luxury.

Challenge consumerism: When companies market products as solutions to loneliness, we can examine if they actually facilitate meaningful connection or simply profit from isolation.

The future of connection

We're at a critical point in how we think about community, connection, and the spaces that facilitate them. And yet, I remain cautiously optimistic. Throughout history, humans have demonstrated remarkable creativity in creating community even under difficult circumstances. The key question is whether we'll recognize connection as a fundamental need worth investing in rather than something to be purchased.

Until next week,

Hanna

Hanna, no shade, “arts and drafts” as a hobby sounds amazing.