The strange psychology of extreme savers

From reusing dental floss to retiring at 25 – unpacking why some people find joy in not spending money (and what it reveals about our money mindsets)...

Hi there, it's Hanna.

Today, we're diving deep into the mind of the frugal — that psychological landscape where saving money isn't just something you do, but something you are. There’s a lot of weirdness to this trend, specifically the kind of weird that makes you wash and reuse ziplock bags or drive an extra 8 miles to save 3 cents per gallon on gas.

As I've fallen down the rabbit hole of frugality content (as one does), I'm wondering: What's the psychology behind extreme saving? Is there a line between frugality and self-imposed deprivation? And what can our relationship with frugality teach us about our money mindsets?

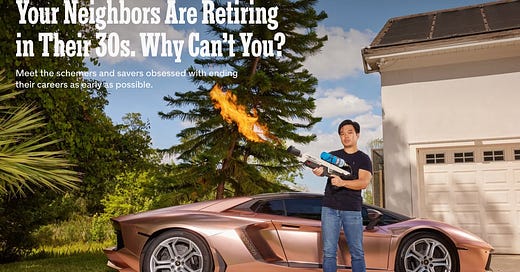

Highly recommend starting with this NYT feature.

Apparently it’s cool to not spend money now

Being thrifty used to just be something your grandparents did after living through the Depression. But over the past few decades, it's become a full-blown cultural phenomenon with its own celebrities, reality shows, and aesthetic.

The spectrum of frugality entertainment ranges from the car-crash fascination of shows like TLC's "Extreme Cheapskates" (where people reuse dental floss and share bathwater) to the aspirational minimalism of Marie Kondo thanking items before discarding them. We're simultaneously horrified and captivated by these extremes.

And, if you've been anywhere near social media lately, you know frugality is having a moment. #underconumptioncore has millions of views on TikTok, showcasing young people embracing minimalism and sustainability. Thrift hauls and DIY projects dominate our feeds.

There are also a crop of frugality influencers, both new and old. People like Bradley on a Budget, the Frugalwoods family, or the granddaddy of them all, Mr. Money Mustache. They all sell a compelling narrative: that spending less isn't deprivation but liberation.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

The FIRE movement: When frugality becomes a fever

No discussion of modern frugality would be complete without addressing the FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early) movement — possibly the most intense frugalists of all.

The FIRE philosophy is effectively frugality with a very specific end goal: save and invest aggressively (often 50-70% of income) to achieve financial independence and retire decades earlier than traditional retirement age. It's frugality as a sprint rather than a marathon.

What started with bloggers has exploded into a subculture with its own terminology and approaches:

Lean FIRE: Extreme frugality to retire on minimal annual expenses (often below $40,000)

Fat FIRE: Higher savings targets for a more comfortable early retirement

Barista FIRE: Working part-time after semi-retiring to cover current expenses

Coast FIRE: Saving enough early so you can "coast" to traditional retirement without adding more

FIRE devotees track their savings rates with the intensity of Olympic athletes monitoring their performance stats, where the trophy is never having to work again.

What's particularly interesting about the FIRE movement isn't just the extreme saving, but the almost religious devotion to the cause. Forums and subreddits are filled with FIRE adherents sharing frugality "hacks" and celebrating milestone "FIRE numbers" with the fervor of evangelists.

The movement reveals something important about frugality psychology: for many, it's not just about the money — it's about control, freedom, and rejecting societal expectations around consumption and career longevity. It's frugality as a revolution against the work-spend-repeat hamster wheel.

The psychological drivers of frugality: What’s really going on?

So what actually drives frugal behavior beyond simple economic rationality?

1. Security

At its core, frugality often stems from a desire for security. Research from behavioral economists like Daniel Kahneman has shown that humans are fundamentally loss-averse — we feel the pain of losses more strongly than we enjoy gains. This asymmetry means that for many people, the psychological comfort of having money saved outweighs the pleasure of spending it.

For some — particularly those who experienced financial insecurity in childhood or lived through economic downturns — frugality becomes a psychological safety blanket. Every dollar saved is a shield against future uncertainty.

2. Control

Frugality provides something increasingly rare in our world: a sense of control. You, yourself, can't control inflation, the job market, the outcome of a presidential election, or global pandemics, but you can control whether you buy that latte.

Psychologist Martin Seligman's work on learned helplessness suggests that having domains of control is essential for mental health. For many frugal individuals, managing their expenses provides that sense of mastery and self-efficacy.

I've noticed this in myself — during particularly chaotic periods, I become more obsessive about tracking expenses and cutting costs. It's not really about the money; it's about having something I can actually control.

3. Identity

In many ways, frugality has become a form of virtue signaling. In our consumption culture, there's moral capital in saying "I don't buy much stuff."

When someone mentions they haven't bought new clothes in years or that they still use a 10-year-old phone, they're not just sharing information — they're making a statement about their values and identity.

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt suggests that moral identity is a powerful driver of behavior. Once frugality becomes part of your moral identity, spending feels like betraying your values rather than simply making a financial choice.

4. Scarcity mindset

A scarcity mindset views resources as limited and depleting — "there's not enough to go around." An abundance mindset believes there are plenty of resources available.

Some frugality is driven by a scarcity mindset — the fear that resources are running out, opportunities won't come again, and you must hold onto every dollar. This can be adaptive in genuinely resource-constrained environments but can become maladaptive when it sticks around despite you reaching financial security.

And of course … *gestures around*

I would be completely remiss not to mention that a lot of frugal and underconsumption behavior is born out of necessity.

While the cost of living continues climbing, paychecks haven't kept pace. When adjusted for inflation, average wages have barely budged since the 1970s despite productivity increasing dramatically.

Plus, the average home now costs 5.6 times the median annual household income — up from 4.7 times in the 1980s. In major cities, it's even worse. Rents have similarly skyrocketed, with many people spending over 50% of their income just to keep a roof over their heads.

The gig economy and contract work have replaced many traditional jobs, adding flexibility but reducing security, benefits, and predictable income — making aggressive saving a necessity rather than a choice.

The dark side of frugality: When savings becomes problematic

Sometimes what looks like financial responsibility can mask deeper psychological issues.

Are you just frugal, or do you suffer from frugality disease?

Some people are frugal because they’re too scared to be anything else. The fear of spending money, known as chrometophobia, is tied to OCD and other compulsive disorders.

Signs include intense anxiety when making even small necessary purchases, sacrificing health, safety, or basic needs to save money, or being unable to enjoy experiences because of constant preoccupation with their cost.

In some cases, frugality can affect one’s relationships. Consider the partner who refuses to participate in any social activity involving money or the roommate who monitors every shared household expense down to the penny. This can easily lead to resentment and tensions.

The time-money tradeoff

Sometimes frugality is penny-wise but pound-foolish. The person who spends hours driving to multiple stores to save a few dollars on groceries may be economically irrational if they could earn more by working those hours.

As financial expert Ramit Sethi says, “Depriving yourself isn’t really living.”

This behavior reveals an intriguing psychological blind spot: we often value money saved more highly than money earned, even when the numbers don't make sense. It's what behavioral economists call the "pain of paying" — saving $10 feels better than earning $10, even though the financial result is identical.

Frugality may mask something deeper

For some people, extreme frugality isn't a choice but a response to financial trauma. Growing up in poverty or experiencing significant financial hardship can create persistent psychological patterns that don't easily change even when circumstances improve.

For example, someone who experienced food insecurity in the past may hoard food. A person who lived through foreclosure might avoid homeownership even when it would be financially beneficial.

Finding a balance with money

Like most aspects of financial psychology, healthy frugality isn't about the specific dollar amount you spend or save — it's about your relationship with that behavior. For example, it could mean:

Choosing frugality based on values and goals rather than fear or compulsion

Being able to spend without excessive anxiety or guilt

Considering both financial and non-financial costs (time, relationships, wellbeing)

Understanding your motivations for frugal behaviors

Viewing money as a tool for creating options rather than a scarce resource

We all exist somewhere on the frugality spectrum — from the big spender to the extreme pennypincher. Where you fall isn't inherently good or bad; what matters is whether your position aligns with your values.

The next time you find yourself thinking about a purchase, ask yourself: What's really driving this behavior? Is it bringing me closer to or further from the life I want?

Because ultimately, frugality — like all financial behaviors — is about much more than money. It's about how we view ourselves, how we relate to others, and what we believe is possible in our lives.

Until next time,

Hanna

I’m frugal because I haven’t ever earned much money and I don’t expect I ever will. Is it any wonder I can’t enjoy spending money? A dollar spent on something unnecessary is a dollar I won’t have for something necessary. Around half of Americans are in a similar financial situation even if they don’t recognize it. I’m always surprised by how many people casually waste money, which to me is a scarce resource.