Everything is private equity <3

Or how my quest to buy a bridesmaid dress ruined by day

I bought a dress for a wedding last month from Reformation. It was $350, which is more than I would normally spend on any item of clothing, but it was silk and I figured that I could wear it again.

When it arrived, it was horrendous.

What I thought I was buying….

The stitching was off. The fabric didn’t feel like silk — and listen, I’m not a fashion person, I wasn’t going to do a burn test on it. But it felt like... fast fashion. Like something you’d get at Zara for $60. Except it was $350.

I had never shopped at Reformation before, but I thought they had a reputation for high-quality, ethical clothes. So I did what I always do when something feels off: I Googled. And there … I discovered it.

All roads lead to Rome, as they say. Except today, all roads lead to private equity.1

Why does everything seem … shittier these days? The quality of your food, your furniture, your clothes is getting worse. Everything that used to be boring and reliable — healthcare, housing, the background infrastructure of daily life — has been quietly acquired, optimized, and hollowed out.

The word for this is enshittification, and while it usually describes tech platforms that slowly degrade to extract more value from users, it applies to the physical economy too. The quality is worse. The service is slower. The bill is higher. And you can’t quite figure out who to blame because the business still has the same name on the sign.

The answer, in many cases, is private equity. <3

The uncanny sameness

Walk into a Sweetgreen in Los Angeles and a Blank Street in New York and a Warby Parker in Chicago and the same designer seems to have touched all of them.

Subway tile, warm wood, sans-serif fonts, Edison bulbs or their spiritual descendants. A plant wall, maybe. Cream and pistachio green and millennial pink. The aesthetic (which I used to call gentrifier core or corporate core) is so ubiquitous it’s become invisible — until you notice it, and then you can’t stop.

The sameness isn’t an accident. These brands are designed to signal a certain kind of authenticity without actually having to be any of those things. They’re not trying to be good at being a coffee shop or an eyeglass store. They’re trying to be good at looking like the kind of company that gets funded, because that’s what they are.

The aesthetic is a pitch deck made physical. And the reason it all blurs together is because the goal was never differentiation. It was pattern-matching to investor expectations. You’re not a customer so much as proof of concept.

This is just the visible layer. What’s happening underneath?

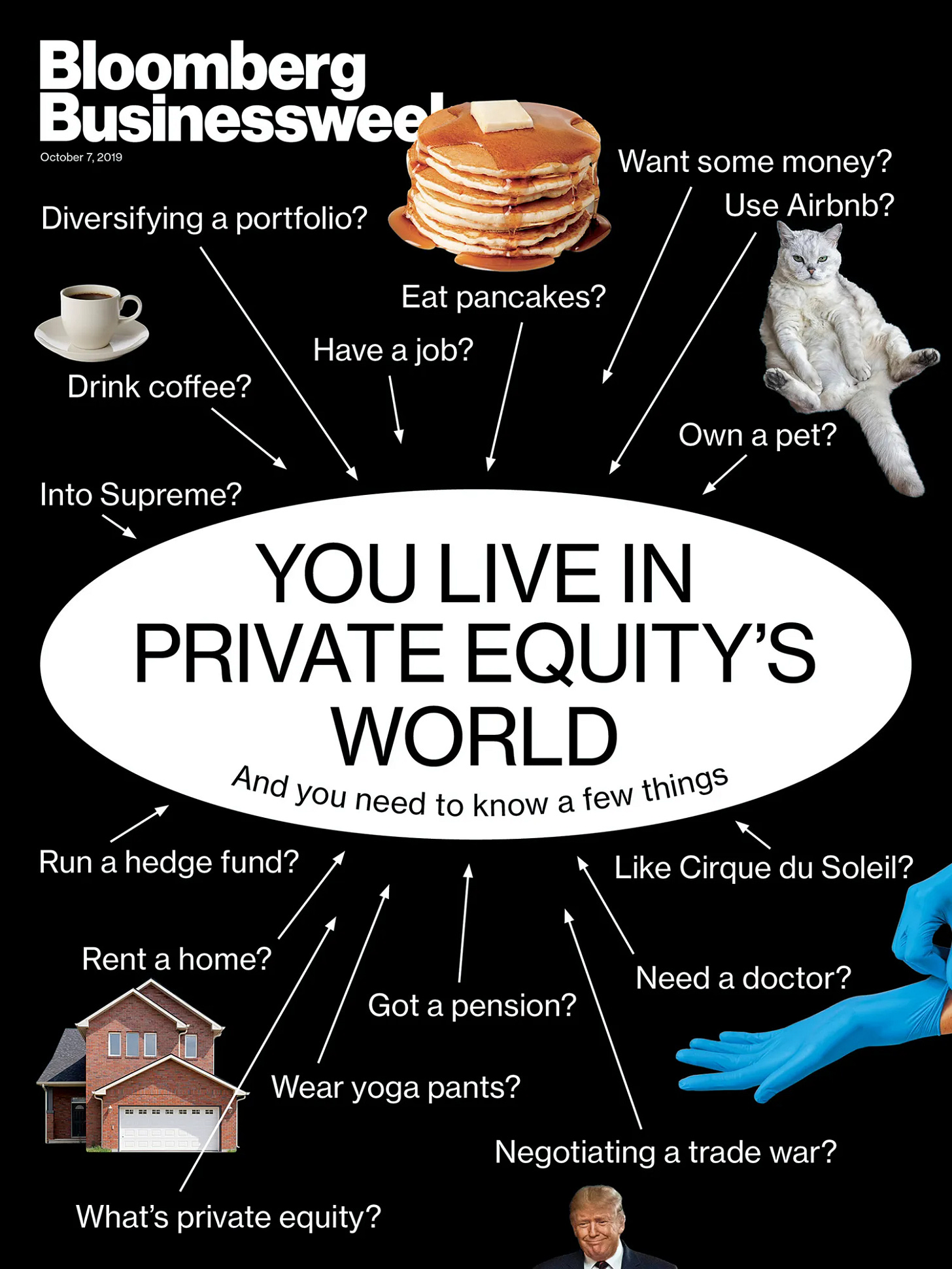

Private equity often operates in the background, buying up all facets of American life. PE now touches nearly every sector of the economy. You could go an entire day — wake up in a PE-owned apartment, drop your kid at a PE-owned daycare, see a PE-owned doctor, pick up dinner from a PE-owned restaurant, come home and watch the local news on a PE-run TV station — without ever encountering a business that operates the way you assume businesses operate.

How the money works (and why it requires making things worse)

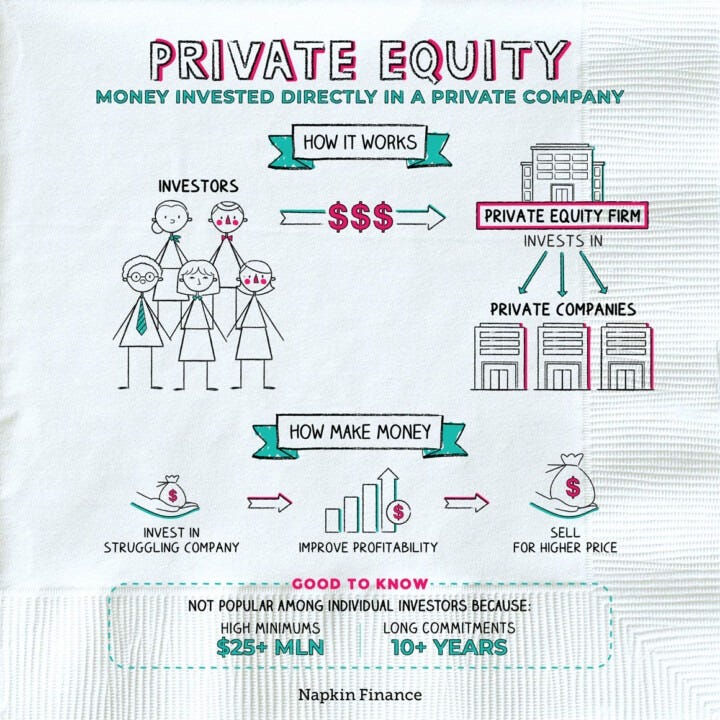

This is my attempt at explaining what private equity firms do, in plain English.

PE firms raise money from big investors — pension funds, endowments, rich people, etc. They use that money (plus a lot of borrowed money) to buy companies. Then they “improve operations” — a very intentionally vague term. After 3-7 years (typically), they sell the company for a profit.

Source: Napkin Finance

The key thing to know is that the debt used to buy the company gets loaded onto the company itself, not the PE firm. So the acquired business has to generate enough cash to service that debt while also delivering returns to investors.

You can see how this model basically requires extraction. When a PE firm buys a veterinary clinic chain at 10x earnings, expecting to sell at 15x, the value has to come from somewhere. That somewhere is usually: raising prices, reducing staff, cutting services that don’t generate revenue, consolidating operations, squeezing suppliers.

This is why PE has particularly targeted industries with fragmented markets (lots of small independent operators), steady demand (people will always need healthcare, housing, childcare), and pricing power (customers can’t easily shop around or delay purchases).

In other words: the essential, boring infrastructure of life. The stuff you have to buy.

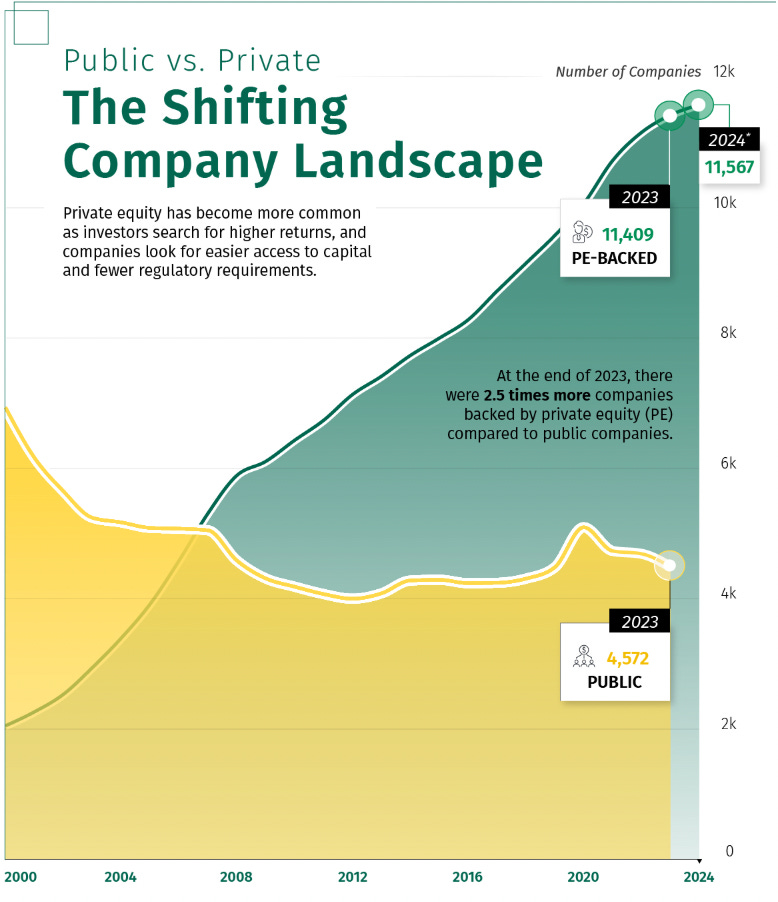

Beyond just the basics, once you start pulling at this thread, you realize PE has woven itself into basically everything. One Harvard professor argues they control as much as 20% of the U.S. economy.

It can’t be that bad, right?

There’s a fairly good chance that PE owns your apartment. Your child’s daycare. Your dentist, your dermatologist, your veterinarian. The urgent care you go to when you catch the flu. Or the emergency room, the ambulance that transported you, the anesthesiologist if you need surgery, and the medical billing company that comes after you when you can’t pay. The pharmacy benefit manager that determines which medications your insurance covers and the addiction treatment center if those medications become a problem.

They may own the stadium where you watch the game and the ticketing platform you bought tickets through. The pizza chain where you picked up dinner beforehand and the gas station where you filled up. The coffee shop you stopped at, the fast-casual lunch spot near your office, the meal kit company that delivers to your door, and the food manufacturers and distributors that stock grocery store shelves.

They may own the gym where you work out and the boutique fitness studio you tried when you got bored. The hair salon where you get your haircut, the nail salon next door, the spa where you got a massage, and the med spa where you considered Botox. The mattress store, the furniture store, the party supply store. The self-storage unit where you keep things that don’t fit in your apartment — which, again, they probably also own.

They own the nursing home where your grandmother lives and the hospice service caring for her at the end. The funeral home that will handle arrangements, the cemetery where she’ll be buried, and the grief counseling service you might use afterward. They own the wedding venue where you got married, the bridal shop where you bought your dress, the photography studio that captured it, and the divorce mediation service if it doesn’t work out.

They own the private school educating your kids and the tutoring center helping them keep up. The pet store where you buy dog food and the doggy daycare where your dog goes during the day. The moving company you hired, the pest control service at your new place, the lawn care company, the plumber, the HVAC repair. The tax prep service, the staffing agency that found you temp work, the background check company your employer used to vet you.

In many cases, they own multiple companies in the same category — creating the illusion of choice. You’re not really deciding anymore, you’re just choosing between different subsidiaries of the same financial investment, optimized for the same outcome: Extracting maximum value from you while you try to live your life.

All of this is done invisibly

PE firms often own portfolio companies through complex holding structures. When they buy a company, they often keep the original name. They’re not required to disclose ownership the way public companies are.

As Molly Osberg wrote in The New Republic, PE’s “central conceit is that financiers, not skilled workers or industry experts, are best positioned to figure out what makes any given business work.”

The people making decisions about your nursing home, your vet, your newspaper — they’ve never worked in healthcare or veterinary medicine or journalism. They work in finance. They see numbers, not people.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

So, shockingly, this business model often leads to everything becoming worse

Private equity's playbook is simple: buy it, squeeze it, profit from it. For consumers, that means higher prices, lower quality, or both. In healthcare, it's literally deadly.

A 2021 study found that PE ownership of nursing homes was associated with a 10% increase in mortality among Medicare patients. This fall, a bipartisan Senate investigation PE-owned hospital chains “prioritized profits over patients,” (complete shocker!) leading to health violations, understaffing, and closures. I recommend this Washington Post investigation on what happened when two PE-backed hospital chains went bankrupt (answer: nothing good!).

PE now staffs approximately 25% of all U.S. emergency rooms. After PE takeover, patient costs rose an average of 80%. A recent study found ER mortality increased 13% at PE-acquired hospitals.

I work for an evil company, but outside of work, I’m actually a really good person!

If you’re truly aware of what PE does — if you understand that the business model often requires making services worse, raising prices, cutting staff, loading companies with debt — how could you possibly support it? Let alone work for it?

I was at a holiday party in Manhattan in December. I knew no one. The room was mostly men in tuxedos, and by the time I’d had my second drink, I’d figured out that about 80% of them worked in private equity.

I would consider myself a polite person, but I am not one to hold my tongue (especially not to a man entering a conversation about finance already under the assumption that he would know more than me because I am a woman). It would take them roughly 30 seconds to tell me what they did and I would respond with, “So — are you gutting nursing homes or destroying farms?”

I was not a hit that night.

The way people that work in PE can rationalize their behavior is mostly centered around willful ignorance and moral licensing, rationalizing behavior they know is problematic through justifications like “everyone else is doing it”.

However, if you work in private equity and genuinely think what you are doing is net-good for society, please read this book. And this article.

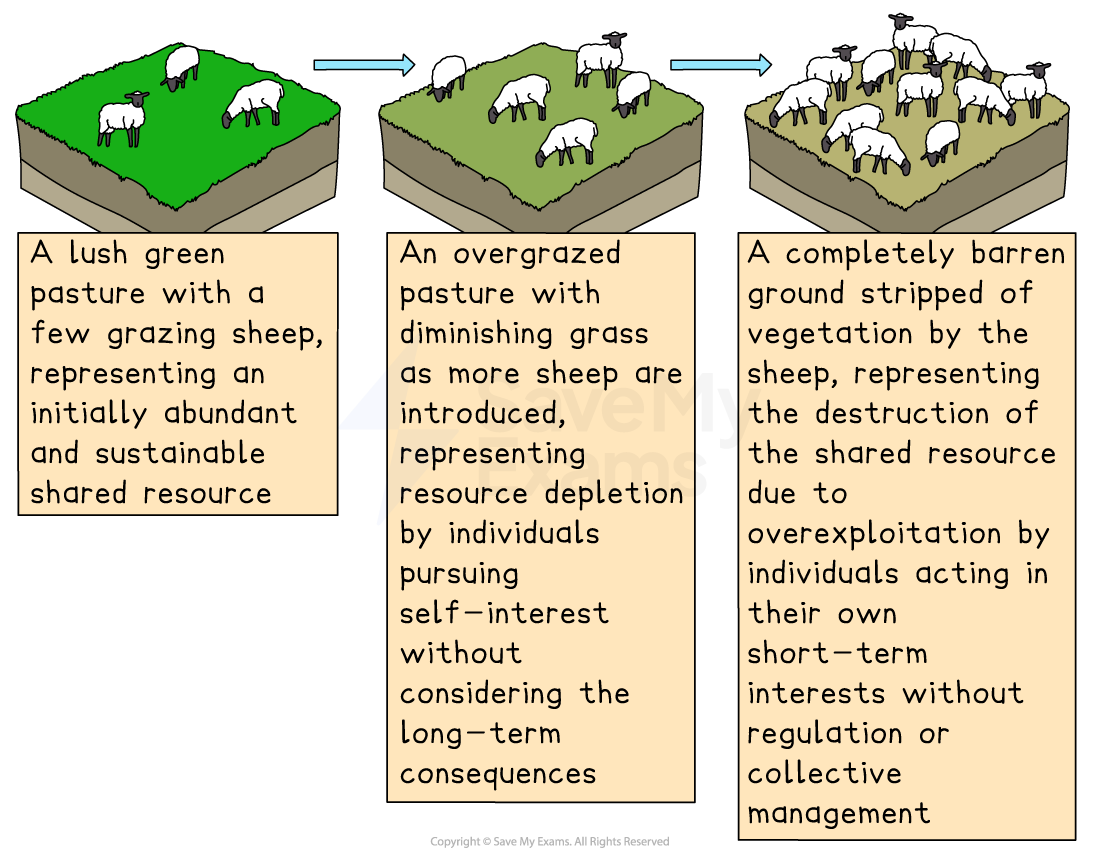

So essentially what you get is a bunch of people making selfish, individual choices that collectively create an extractive system where everyone can claim they’re not personally responsible. It’s a classic tragedy of the commons

So … what now?

And look. I get it. We all do things to pay the bills. Yes, we’re all implicated in harmful systems. But there’s a difference between “I’m complicit by participating in capitalism” and “I’m actively creating systems that maximize extraction.” The first is unavoidable, the second is a choice.

At some point, you have to decide: Do you want to directly contribute to the enshittification of the daily life, or not?

It’s very, very easy to throw up your hands and say there’s nothing you can do. It’s harder to take the time to think about and act on using whatever power you have in productive ways. This could mean organizing in your workplace, supporting (or running for) local office, voting, volunteering, choosing to work for places that aren’t actively extractive when you have that privilege.

And we have to keep remembering that while these large companies feel nameless and shadowy and too big to fail, there’s a very real human cost at the end of the line. Megan Greenwell wrote a book about this called Bad Company. There’s a line in it I keep coming back to:

“When we talk about how private equity affects communities, we’re really talking about how it affects people — the individuals who have no choice but to rely on firms for their jobs, their homes, their essential services.”

We’re all those individuals now. Whether we know it or not.

A majority Reformation was bought by PE in 2019 and has rapidly grown since then. They’ve also increased their carbon emissions and shifted to cheaper synthetic fabrics while keeping the luxury prices and the sustainability marketing.

Great piece. I've also read recently that PE is having a hard time selling investments and is getting lower returns lately. They run these businesses into the ground and then try to sell them. Who wants to buy the business?

This is something I really want Congress to do something about. Private equity ruins everything. It's disheartening to know how many public pensions are tied up in it

And don't forget colleges and universities, who have over the past several decades years have increasingly invested their endowments in private markets and whose boards are filled with people who work in private equity. (And their investment offices are filled with PE alum). It's a great model for education!